Government-ordered lockdowns designed to slow the virus' spread hurt manufacturing and triggered a big shift in how people spent their money.

The shortage issues caused by the soft forecast for 2020 worsened as the coronavirus spread around the world.

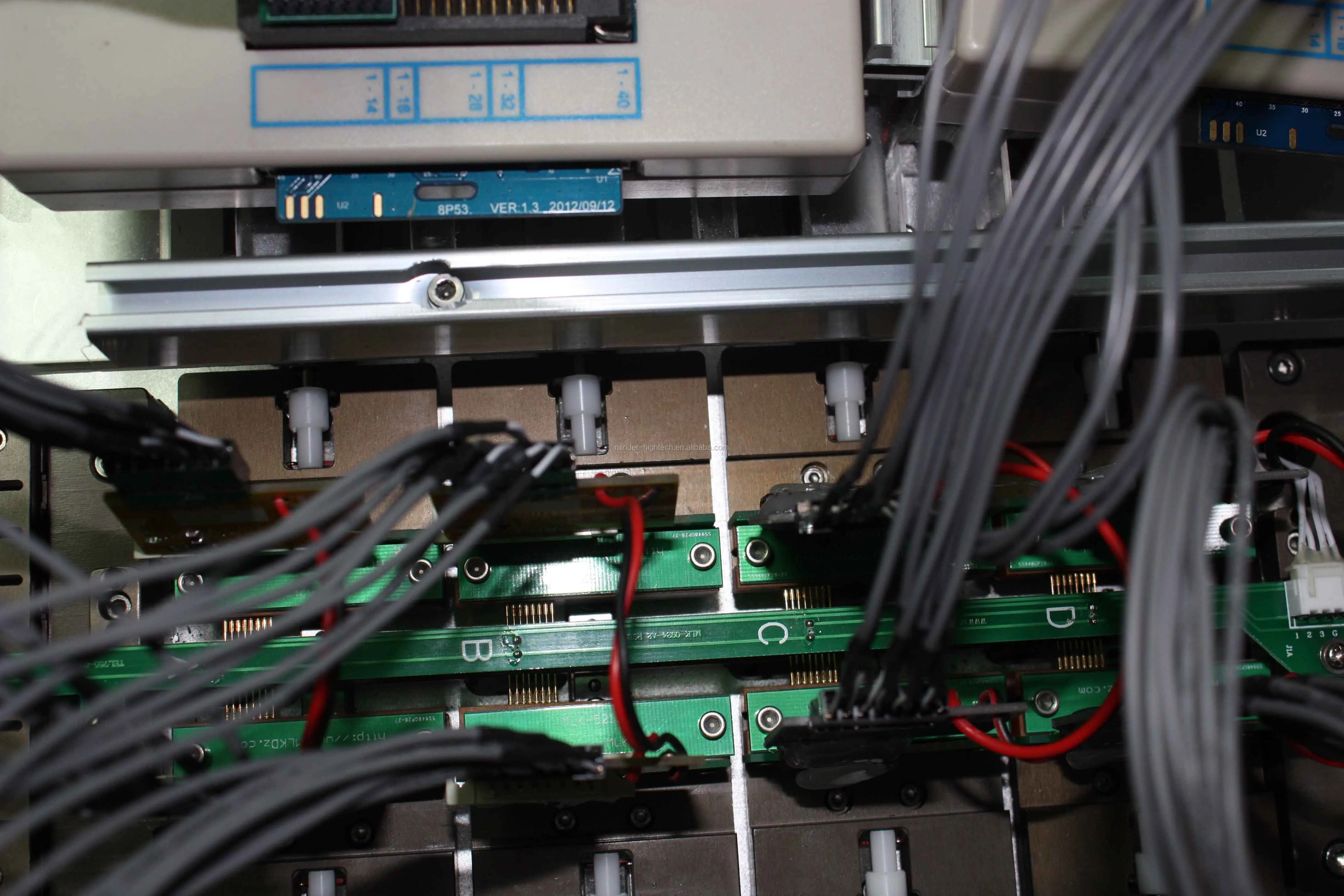

"When the pandemic hit, it just threw everything out the window as far as their forecasting capabilities because they didn't see this coming," Penfield said. The coronavirus threw those plans into the blender. Toward the end of 2019, some companies forecast that demand for chips was going to drop slightly in 2020, according to Intel's Greg Bryant, vice president of the client computing group. The market conditions ahead of the COVID-19 pandemic weren't particularly favorable for the chip industry, either. "Chip manufacturers use what's called a lag-type capacity strategy, so they will wait to see if the demand is there and then they'll go ahead and build the capacity," Penfield said. And there are only two companies that can make the most advanced chips for third parties right now: TSMC and Samsung Electronics.īecause of the enormous cost of building new plants, companies are loath to build manufacturing capacity that executives think will ever sit idle. Executives make production decisions months in advance, especially to secure the most advanced manufacturing capabilities needed to make chips that power iPhones and supercomputers.Įxpanding that manufacturing capacity requires tens of billions of dollars, thousands of skilled workers and months or years to construct the facilities. Semiconductor manufacturing is an incredibly complex and expensive business, and it can take years to adjust to big changes in demand. None of this has been lost on corporate America, which has mentioned the chip shortage 3,247 times in corporate earnings calls, presentations and filings so far this year, compared with seven times in 2020 and almost never in years prior, according to data from corporate research platform Sentieo. "It's a multidimensional problem," Maribel Lopez, founder of Lopez Research, told Protocol.

It took the well-known complexities involved with chipmaking coupled with a generational shift in computing, both of which were further aggravated by the economic changes wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic. Getting to this point has not been a straightforward or obvious path, even with the benefit of hindsight. It'll get into stores and they're going to have to mark down a lot of that seasonal stuff."īut it's hard to know exactly how the shopping season will play out over the next few weeks, and some patience - never easy to come by on Black Friday - will likely be required. "Eventually it all comes to roost when, which is eventually going to happen in the first and second quarter. "What happens is the whole supply chain gets filled with all these materials," he said. According to Whitman School of Management professor of supply chain practice Patrick Penfield, shortages may lead to over-ordering, which might force retailers to sell excess seasonal inventory at a discount. It's possible there will be some relief for consumers next year. "You better start shopping sooner rather than later, and once you see it, regardless of that price in retail, you need to buy it or you risk not getting it," CEO and principal analyst at Creative Strategies Ben Bajarin told Protocol. The expert advice? Get it early, expect to overpay and don't hesitate. Thanks to a global run on the silicon chips that power just about every consumer product ranging from refrigerators to next generation video game systems, this holiday shopping season is probably going to be one of the most unusual many of us will experience. By the time you read this, if your holiday shopping includes just about anything that needs a computing chip, it might be better to wait until next year to buy it.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)